Concurrent Training Considerations

Welcome to the latest issue of The Football Scientist.

In this week's issue, I'm going to provide practical considerations and advice on how to plan concurrent training programmes.

I hope you enjoy!

What is Concurrent Training?

Concurrent training refers to the simultaneous integration of resistance and endurance exercise into a periodized training regime.

The majority of sports require some combination of both resistance (strength, hypertrophy, power) and endurance aspects.

Team sports are one of the best examples of this notion. A soccer player must cover significant distances at both low and high speed, but at the same time must engage in physical contact (e.g. duel for the ball).

The requirements can also differ depending on positional role within a team.

Let's take rugby league as an example. Props are typically the heaviest players and have to essentially act as a battering ram to gain meters. Whereas a winger will be smaller in size and required to produce more explosive efforts at higher speeds across the duration of the match.

There are of course certain sports at differing ends of the training spectrum.

Strongman athletes typically focus solely on resistance training. Whereas a Tour de France cyclist will predominantly be focused on endurance work, with some injury prevention type resistance exercises included.

To note, there is growing popularity in 'hybrid' trained athletes. This is essentially where an athlete is trying to become better to both endurance and resistance training sports simultaneously (think 500lb squat and sub 5 minute mile in the same day). Crossfit is a good example of this notion, although I would suggest looking up Fergus Crawley and Nick Bare on Google to see some of their incredible feats as hybrid athletes.

Concurrent training differs as typically the combination of exercise modes is for one to supplement the other.

The Interference Effect

Back in 1980, Robert Hickson published his novel study suggesting a possible interference effect between strength and endurance adaptations.

He observed reduced strength gains in 1RM back squat testing over a 10 week period when participants added endurance training to their strength programme compared to a strength only group.

This study was the first to produce peer reviewed data on a training topic that anecdotally people experienced for many years.

The publication of this study led to a new area of research for sports scientists and physiologists to explore both in the lab and field. A quick PubMed search reveals over 16,000 papers published since 1980 in this area.

So, what are the possible causes of this observed 'interference effect'?

The work of Vernon Coffey and John Hawley investigating the molecular pathways involved with both single and combined modes of training have helped shed light on this phenomenon.

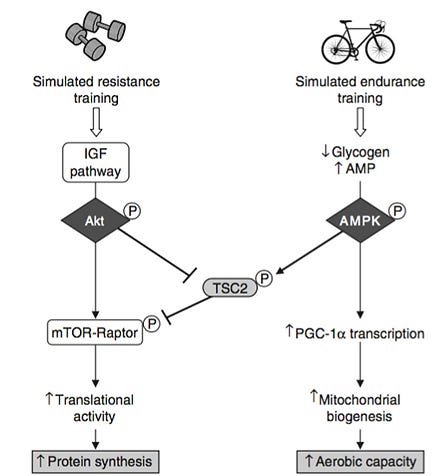

Below is an image that highlights the potential molecular pathways for both resistance and endurance training adaptation taken from Coffey et al. (2007).

In terms of resistance training, it has been suggested that mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a key regulator of protein and muscle synthesis. Conversely, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) has a key role in mitochondrial biogensis (in other words, the creation of new mitochondria within the cell).

However, AMPK also has a key in the regulation of muscle protein synthesis for growth. Therefore, it would seem logical that concurrent training (i.e. the activation of both molecular pathways) may potentially play a role in the supposed interference effect.

Others factors that may influence adaptation include different training intensities, hormonal responses, order of concurrent training and recovery time between bouts.

For many years, those at opposite ends of the training spectrum have feared the opposing exercise mode.

For example, bodybuilders had the mind set that even a small amount of cardio (e.g. 30 min easy cycle) would cause all of their muscle to drop off!

Same with endurance athletes, they perceived lifting weights as making them heavy and reducing performance.

But what does the latest research tell us?

If you are an endurance athlete, then adding resistance training in a progressive way will actually enhance your performance. A good example of this is when runners include strength and plyometric type exercises to their programme, which can actually enhance running economy and thus performance.

If you are a resistance training based athlete, then adding too much endurance will certainly result in less than optimal adaptation. However, some endurance training (2-3 times per week) performed at low intensity can actually help firstly body composition management but also help improve recovery time between sessions.

Concurrent Training and Team Sports

So far we have mainly focused on single exercise mode sports. However, what about team sports that often require both?

There is often a trade off between what the science tells us and the practicalities of training planning.

Let's use an example in soccer.

The team has a normal one game week on a Saturday, with 4 main pitch based soccer sessions that week.

This means there is opportunity to include 2-3 resistance training sessions within the programme. This will be mainly focused on injury prevention and some progressive exercises to enhance or maintain physical qualities.

Now the literature would suggest at least 6 hours of recovery between the AM pitch based sessions and the resistance training session (e.g. 10am pitch, 4pm lift). However, practically most players want to condense training into 2-3 hours so they can leave and get on with other things in their lives (e.g media commitments, sponsorship events).

Some players will prefer then to do the pitch session, immediately followed by the gym-based lifting session.

This creates potential adaptation issues, as carrying excessive fatigue from the pitch session can lead to sub-optimal resistance adaptation in the subsequent gym session. From my experience, players will come into the gym tired and often skip exercises, reduce sets/reps of the planned programme or don't lift with the required intensity.

Some players prefer to lift first (say 9am) and then head out to the pitch session. However, this can again lead to fatigue in the second session and research has shown negative effects on chronic endurance adaptation.

Therefore, the advice here would be to prioritize the most important session for the sport/training block and focus on this first. If possible separate out the sessions to allow sufficient recovery.

Thank you for reading, see you next week.

Whenever you're ready, check out how I can help you further:

Football Fitness Mentorship Community: Are you a football fitness practitioner looking to accelerate your career? Join an exclusive online mentorship community of football fitness practitioners and access resources, educational content, 1:1 support and a worldwide network. The community is aimed at football fitness practitioners - whether you are a student with future aspirations to work in football, an early career practitioner still finding their way or experienced practitioners looking to progress their career further. Check it out here.