How to Implement Tactical Periodisation in Football

Thank you to our partners who keep this newsletter free to the reader:

Stay ahead of the competition by learning how to code with R. Check out the Level 1 R for Sport Science course and learn in only 5 weeks!

Use the code ‘MALONE50’ for an exclusive discount. Click here to find out more

There are many ways to skin a cat.

This notion can be applied to football periodisation.

Throughout the years, coaches have developed different periodisation models and ways of planning to optimise performance.

You have the British model with days off within the week.

You have the Raymond Verheijen model focusing on football actions.

In recent years we have seen the emergence of Tactical Periodisation as a common way to plan training microcycles in football.

Originating in Portugal, tactical periodisation is centred around training the four moments of the game: attacking organisation, defensive organisation, attacking transition and defensive transition. This is also known as the ‘game model’.

Despite its popularisation, there are questions around how it can be implemented practically, particularly with teams who regularly have congested fixture periods across the season.

This week’s newsletter will discuss the key considerations when implementing tactical periodisation in football.

Let’s dive in.

The Tactical Periodisation Model

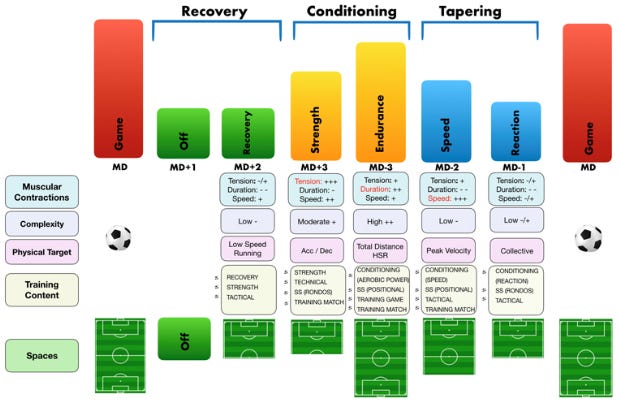

During a normal one-game week, the model is relatively straightforward.

Following the previous game, there is a two-day recovery phase on MD+1 and MD+2.

This is followed by a four-day loading phase from MD-4 to MD-1 in the build up to the next game.

On MD-4 and MD-3, the physical load is at its highest, with MD-2 and MD-1 seen as a mini taper phase to reduce fatigue and increase readiness.

MD-4 is focused around ‘strength’ as a training theme.

From a coaching perspective, this involves a lot of small-spaced games (e.g. possession drills, small sided games). From a physical perspective, the focus is around accelerations, decelerations and changes of direction.

MD-3 allows a more open space for the ‘endurance’ training theme. This is where medium-large sided games and transition drills are mainly used, with high speed and sprint efforts the physical focus.

MD-2 still allows opportunity for physical loading in the form of ‘speed’ training. For this day, think quality > quantity where the intensity is high but duration in low.

MD-1 then transitions into the upcoming game with a light session centred around tactical preparation.

Differences with Turnaround Times

The model works well when there is a normal turnaround time.

However, for teams who regularly play two games or more a week, the model has to be adapted to allow for recovery and preparation between games.

The idea is that the ‘theme’ days are still evident, but essentially during fixture congestion certain days become less frequent.

Below is an example breakdown for starters playing a two-game week:

Wednesday (MD-1): Game 1

Thursday (MD+1): Recovery (Light session + tactical reflection)

Friday (MD-2): Tactical reinforcement (Focused tactical drills + SSGs)

Saturday (MD-1): Pre-match Activation (Light technical drills + Tactical review)

Sunday (MD): Game 2

The same can be true of situations such as 5-day turnarounds.

Typically, the model will always allow for the 2-day recovery phase, so essentially the loading phase goes from 4 to 3 days in a 5-day turnaround. Below is an example:

Saturday (MD-1): Game 1

Sunday (MD+1): Recovery (Active recovery + Tactical reflection)

Monday (MD+2): Day Off

Tuesday (MD-3): Endurance Theme (High-intensity tactical scenarios)

Wednesday (MD-2): Speed Theme (Set-pieces + Tactical fine-tuning)

Thursday (MD-1): Pre-match Activation (Light technical drills + Tactical review)

Friday (MD): Game 2

Limitations of Tactical Periodisation

I have worked under a number of different coaches and seen various models and microcycle formats used.

Tactical periodisation is a nice framework as it incorporates different aspects of training (physical, technical, tactical, psychological) into a structured model.

However, like all models it can have its downsides too.

From my experience, there is a lot of emphasis on the training session itself providing the physical conditioning for the players.

This includes warm ups and conditioning drills which are often short in length and typically done with the ball.

Whilst this can get good buy in from players, it can also neglect more general physical conditioning that could be achieved through more isolated approaches (e.g. MAS conditioning).

This is also particularly evident for youth players transitioning to 1st team level. It can be very much a ‘sink or swim’ approach due to the high demands of tactical periodisation training.

There is also a general lack of days off with this model. Some coaches are better than others at this, but it’s certainly not uncommon to have only a handful of days off for players each month during the in-season phase.

Take Home Messages

Tactical periodisation is widely used at different levels of the football pyramid.

If used correctly, it can potentially enhance performance during the in-season phase.

Below are some key take home points around implementing tactical periodisation in football:

- Use the different physical ‘theme’ days across your microcycle.

- Adapt the model according to the days within each turnaround time.

- Understand the downsides of tactical periodisation, particularly for younger players.

- Ensure you schedule enough days off for players to prevent burn out.

If you would like to learn more about how to use tactical periodisation for football training, check out my football fitness mentorship community here.

That’s all for this week. See you next time!