Managing Progression From Youth to Professional Football

Last week I was fortunate enough to travel to a few clubs as part of my BASES (now CASES) accreditation work.

During my trip, it was really interesting to see the contrasts between an academy category 1 set up with that of a team with lower resources (category 3 academy).

The first thing that struck me was the number of staff. I was in the office at the category 1 club and it was full with physical performance coaches, sports nutritionists, data scientists and students on placement.

Contrast that with the category 3 academy, which had pretty much two physical performance staff (plus one placement student) supporting the whole programme.

But interestingly the principles observed at both clubs were similar.

I saw some fantastic work being done in the gym by both teams, with similar observations being noted with the on-pitch conditioning too.

So obviously whilst budget and resources will have a significant impact on developing youth players, it got me thinking as to what actually matters from a physical performance perspective when it comes to managing progression.

This paper from James Dugdale and colleagues provided a longitudinal view of 537 youth footballers progression based on fitness test performance.

The authors found that only 10% of players were successful in obtaining a professional contract.

68% of players who became professional were recruited at 12 years of age or older.

Successful academy graduates only physically outperformed unsuccessful counterparts from age ~13-14 years onward, with no differences during childhood or early adolescence.

From a training load perspective, we see clear differences in the intensity demands when transitioning from youth-to-senior football.

This study by Kobe Houtmeyers and colleagues revealed higher sprint distance (>25 km/h) during both one and multiple game weeks for senior vs. U19 players.

It is something I’ve also seen in practice. When academy players begin to train with the 1st team, most initially struggle with the intensity of training.

Some will stabilise and adapt to the demands. Others crash and burn, struggling to physically maintain the required intensity of senior football - sometimes leading to injury.

This can also be coupled with youth players being sat on the 1st team bench and not getting any match exposure. They then need to make up for this by playing for the academy team, which is sometimes not aligned to the 1st team schedule.

When training within the academy setting, naturally the coaches will want to stop the play to get across their coaching points.

From a physical perspective, depending on the targets/theme for the day, it can lead to sub-optimal loading. It can be a tricky balance that requires clear communication between the coaching and physical performance staff.

A recent study from Alberto Franceschi’s PhD provided a detailed comparison of training load across U15-19 teams within an elite Italian academy.

Interestingly, the heart rate response (>85% and >90% HRmax) was much higher in the U15 group compared to the U19 group.

This is despite the sRPE training load being highest in the U19 group.

The authors speculated that the higher heart rate in the younger age groups were due to more technical skill-based drills in small groups, compared to larger tactical drills (e.g. phase of play) in older age groups.

We are also seeing a trend of overplaying talented players at very young ages.

Lamine Yamal at Barcelona has now made over 100 senior appearances (including 19 games for the Spanish senior national team) by the age of 17 and 275 days old.

This potential risk for young players was highlighted in the most recent FIFPRO players union report.

The pathway for each players progression into the first team can be completely different.

For every player like Yamal you have one like Harry Kane - who went on loan to 4 separate clubs before making his breakthrough at Tottenham.

David Flower, Everton FC senior academy sport scientist, has been examining the factors around academy progression as part of his Professional Doctorate.

He found that all the U21 players trained with another squad across the season.

90% of the U18 group also trained with another squad. Whereas first team players trained 100% within the first team set up.

This left some players being under-exposed to training and completion of the programme within the academy.

We have also seen the loan pathway being used to provide exposure to senior football with great success (such as Harry Kane).

This has led to new roles being created in football, such as loans pathway sport scientist, to better manage the training of loan pathway players.

There is no exact playbook for a players transition from youth-to-senior football. Everyone has a different pathway.

However, some principles should be adhered to:

Progressive exposure to senior football - manage weekly loads and fixture frequency.

Load management and monitoring - don’t ignore the monitoring of internal load to understand how a player is coping with the external load.

Recovery and lifestyle - educating players on how to live like a professional, effective recovery and general lifestyle.

If you are interested in learning more about managing the transition from youth-to-senior football from an internal load perspective, next month I will be doing a free webinar in collaboration with Firstbeat Sports. Register here.

Bottom Line - There is no exact playbook for youth-to-senior player progression. You have to treat each player individually and use the key training principles to carefully manage the load and progression over time.

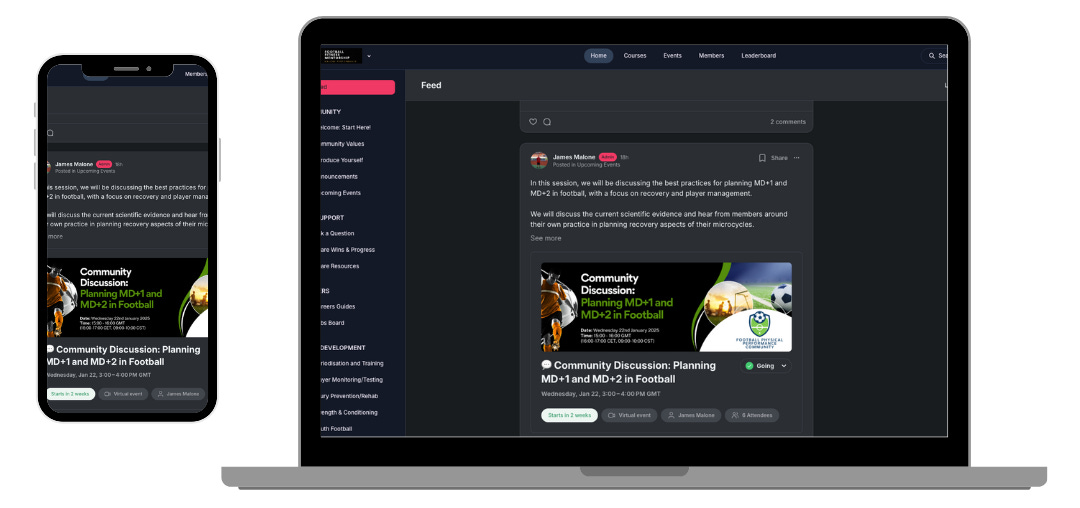

Join The Football Physical Performance Community

Don’t miss your chance to join a global network of practitioners to gain access to 1:1 mentorship, live events with industry leading speakers and enhance your skills through educational content.

Take charge of your career and achieve your goals with expert guidance and resources.

Join 60+ physical performance practitioners as part of a supportive community.

See you next week!

James