Monitoring Training Load in Goalkeepers

Welcome to the latest issue of The Football Scientist.

In this week's issue, I will be discussing the research literature around the training and monitoring practices of a forgotten position in soccer - the goalkeeper.

I hope you enjoy!

Role of a Goalkeeper

The position of goalkeeper is one of the most crucial roles in soccer.

The last line of defence in which mistakes typically leads to a goal for the opposition.

If you think of all the top sides down the years, they all have one thing in common - a top goalkeeper.

Essentially, they are now considered part of the 11 outfield players, as opposed to 10+1, due to their higher requirement to use their feet to play out from the back.

So, from a sports science perspective, what is currently available to guide training and monitoring practices?

Demands of a Goalkeeper

The typical match day load of a goalkeeper is around 5.5km of total distance, around 50-100m sprint distance and 5-10 high accelerations/decelerations.

Interestingly, the position of goalkeeper is one in which the training load pattern is actually 'flipped' in comparison to other positions.

Rather than periodizing the training load from MD-5 to MD-1, with the MD being the highest load, the match day itself will be a goalkeeper's "easiest" loading day, with training being harder days in the build up.

This was highlighted in a study by White et al. (2020), revealing all goalkeeper metrics (expect high speed distance covered) were higher in GK-specific drills across the training microcycle compared to match day.

Typically, GKs will train as part of a small group (3-5 keepers) away from the outfield players, then join up in the main training at specific points, such as during small sided games, tactical work, set pieces, etc.

When conducting individual training with the GK coach, drills include shot stopping, distribution drills, catching and diving/reactions amongst others.

It's also fairly common for the GK group to start training earlier than outfield players, before joining up with outfield player drills and even doing post main training activities. Therefore, overall training duration each day tends to be high.

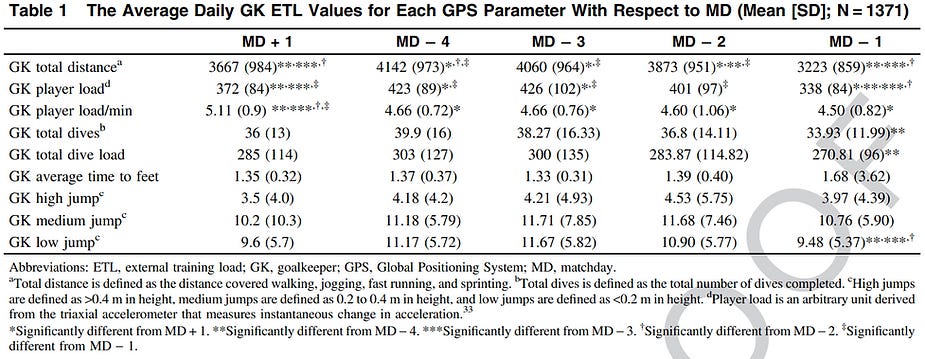

We can see from the below table taken from Grimson et al. (2023) that the training load of goalkeepers is fairly consistent most days within the microcycle.

In our own research (Malone et al. 2017), we found MD-1 tended to be lower compared to other days in the microcycle.

Therefore, the periodisation may be dependent on the specific goalkeeper coaches within certain clubs. In my own experience, MD-1 does still tend to be shorter in duration and overall load for GKs.

Monitoring Goalkeeper Load

In the past, goalkeepers were often neglected when it came to athlete monitoring.

Some used RPE-based metrics to keep track of internal load. Others used heart rate but had issues with the belts slipping down due to the diving movements.

The use of GPS devices was introduced to goalkeepers but using traditional metrics, such as total distance, distances in zones and accels/decels.

The problem with this approach is the lack of specificity to the position.

For example, sprint distance is very minimal (50-100m) in matches and even in training, so wouldn't be the ideal metric to use.

Total distance may be useful in some regard as a general training volume measure, but again it doesn't help quantify the GK-specific movements.

When I worked at Catapult Sports, I was part of a project that helped to develop the first GK-specific devices that provides specific metrics such as dives, time to feet and jumps.

These metrics were used in the two studies mentioned earlier (White et al. 2020 and Grimson et al. 2023).

However, to my knowledge, there has been no peer-reviewed validation of these metrics in published research. This has been on my research list for a while and certainly needs doing.

Interestingly, Grimson et al. (2023) found only small to trivial correlations between the new GK metrics and subjective wellness markers.

It would be interesting to firstly validate these metrics but also use objective GK specific testing to understand the dose-response relationship with GKs over time.

For now, the use of RPE arguably still provides the best measure of load with GKs, with the new GK metrics providing further insight but questions about whether they are sensitive to changes in load.

Thank you for reading, see you next week.

🚀 Join The Football Performance Network

Take your career in football to the next level by joining a global community of 60+ physical performance practitioners.

As a member, you'll get:

✅ Direct 1:1 mentorship

✅ Weekly live events with industry-leading experts

✅ Practical, high-quality educational content

✅ A supportive network that understands your journey

Whether you're looking to grow your skills, make better decisions in your role, or build your career in elite football, this is the place to do it.

🔗 Join now and start learning, connecting, and progressing — together.